CHAPTER XV—THE NORTHERN ARMIES

Enlisting (1861–1864)

BY JOHN DAVIS BILLINGS (1888)

THE methods by which these regiments were raised were various. In 1861 a common way was for some one who had been in the regular army, or perhaps who had been prominent in the militia, to take the initiative and circulate an enlistment paper for signatures. His chances were pretty good for obtaining a commission as its captain, for his active interest, and men who had been prominent in assisting him, if they were popular, would secure the lieutenancies. On the return of the "Three months" troops many of the companies immediately re-en-listed in a body for three years, sometimes under their old officers. A large number of these short-term veterans, through influence at the various State capitals, secured commissions in new regiments that were organizing. In country towns too small to furnish a company, the men would post off to a neighboring town or city, and there enlist.

In 1862, men who had seen a year’s active service were selected to receive a part of the commissions issued to new organizations, and should in justice have received all within the bestowal of governors. But the recruiting of troops soon resolved itself into individual enlistments or [on?] this programme;—twenty, thirty, fifty or more men would go in a body to some recruiting station, and signify their readiness to enlist in a certain regiment provided a certain specified member of their number should be commissioned captain. Sometimes they would compromise, if the outlook was not promising, and take a lieutenancy, but equally often it was necessary to accept their terms, or count them out. In the rivalry for men to fill up regiments, the result often was officers who were diamonds in the rough, but liberally intermingled with veritable clodhoppers whom a brief experience in active service soon sent to the rear.

This year the War Department was working on a more systematic basis, and when a call was made for additional troops each State was immediately assigned its quota, and with marked promptness each city and town was informed by the State authorities how many men it was to furnish under that call. . . .

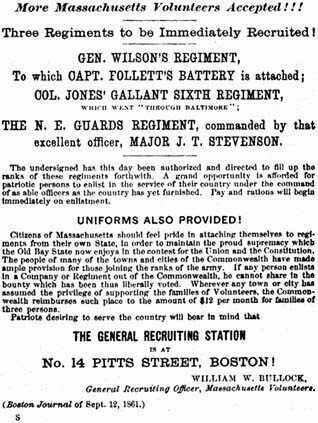

The flaming advertisements with which the newspapers of the day teemed, and the posters pasted on the bill-boards or the country fence, were the decoys which brought patronage to these fishers of men. Here is a sample:—

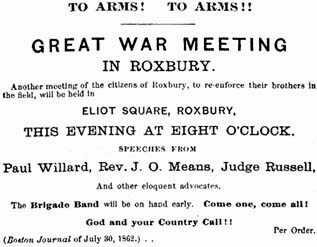

Here is a call to a war meeting held out-of-doors:—

War meetings similar to the one called in Roxbury were designed to stir lagging enthusiasm. Musicians and orators blew themselves red in the face with their windy efforts. Choirs improvised for the occasion, sang "Red, White, and Blue" and "Rallied ’Round the Flag" till too hoarse for further endeavor. The old veteran soldier of 1812 was trotted out, and worked for all he was worth, and an occasional Mexican War veteran would air his nonchalance at grim-visaged war. At proper intervals the enlistment roll would be presented for signatures. There was generally one old fellow present who upon slight provocation would yell like a hyena and declare his readiness to shoulder his musket and go, if he wasn’t so old, while his staid and half-fearful consort would pull violently at his coat-tails to repress his unseasonable effervescence ere it assumed more dangerous proportions. Then there was a patriotic maiden lady who kept a flag or a handkerchief waving with only the rarest and briefest of intervals, who "would go in a minute if she was a man." Besides these there was usually a man who would make one of fifty (or some other safe number) to enlist, when he well understood that such a number could not be obtained. And there was one more often found present who when challenged to sign would agree to, provided that A or B (men of wealth) would put down their names. . . .

Sometimes the patriotism of such a gathering would be wrought up so intensely by waving banners, martial and vocal music, and burning eloquence, that a town’s quota would be filled in less than an hour. It needed only the first man to step forward, put down his name, be patted on the back, placed upon the platform, and cheered to the echo as the hero of the hour, when a second, a third, a fourth would follow, and at last a perfect stampede set in to sign the enlistment roll, and a frenzy of enthusiasm would take possession of the meeting. The complete intoxication of such excitement, like intoxication from liquor, left some of its victims on the following day, especially if the fathers of families, with the sober second thought to wrestle with; but Pride, that tyrannical master, rarely let them turn back.

John D. Billings, (Boston, etc., 1888), 34–41 passim.