The Measurement of the Circumference of the Earth

Cleomedes

About the size of the earth the physicists, or natural philosophers, have held different views, but those of Posidonius and Eratosthenes are preferable to the rest. The latter shows the size of the earth by a geometrical method; the method of Posidonius is simpler. Both lay down certain hypotheses, and, by successive inferences from the hypotheses, arrive at their demonstrations.

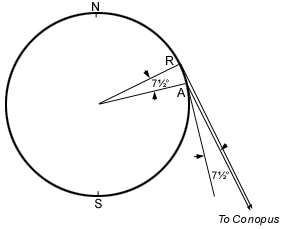

Posidonius says that Rhodes and Alexandria lie under the same meridian. Now meridian circles are circles which are drawn through the poles of the universe and through the point which is above the head of any individual standing on the earth. The poles are the same for all these circles, but the vertical point is different for different persons. Hence we can draw an infinite number of meridian circles. Now Rhodes and Alexandria lie under the same meridian circle, and the distance between the cities is reputed to be 5,000 stades. Suppose this to be the case.

All the meridian circles are among the great circles in the universe, dividing it into two equal parts and being drawn through the poles. With these hypotheses, Posidonius proceeds to divide the zodiac circle, which is equal to the meridian circles, because it also divides the universe into two equal parts, into forty-eight parts, thereby cutting each of the twelfth parts of it (i.e., signs) into four. If, then, the meridian circle through Rhodes and Alexandria is divided into the same number of parts, forty-eight, as the zodiac circle, the segments of it are equal to the aforesaid segments of the zodiac. For, when equal magnitudes are divided into (the same number of) equal parts, the parts of the divided magnitudes must be respectively equal to the parts. This being so, Posidonius goes on to say that the very bright star called Canopus lies to the south, practically on the Rudder of Argo. The said star is not seen at all in Greece; hence Aratus does not even mention it in his Phaenomena. But, as you go from north to south, it begins to be visible at Rhodes and, when seen on the horizon there, it sets again immediately as the universe revolves. But when we have sailed the 5,000 stades and are at Alexandria, this star, when it is exactly in the middle of the heaven, is found to be at a height above the horizon of one-fourth of a sign, that is, one forty-eighth part of the zodiac circle. It follows, therefore, that the segment of the same meridian circle which lies above the distance between Rhodes and Alexandria is one forty-eighth part of the said circle, because the horizon of the Rhodians is distant from that of the Alexandrians by one forty-eighth of the zodiac circle. Since, then, the part of the earth under this segment is reputed to be 5,000 stades, the parts (of the earth) under the other (equal) segments (of the meridian circle) also measure 5,000 stades; and thus the great circle of the earth is found to measure 240,000 stades, assuming that from Rhodes to Alexandria is 5,000 stades; but, if not, it is in (the same) ratio to the distance. Such then is Posidonius’ way of dealing with the size of the earth.

RA (Rhodes—Alexandria) = 5,000 stades. The star is assumed to be so distant that the lines to it from R and A may be considered parallel.

RA (Rhodes—Alexandria) = 5,000 stades. The star is assumed to be so distant that the lines to it from R and A may be considered parallel.

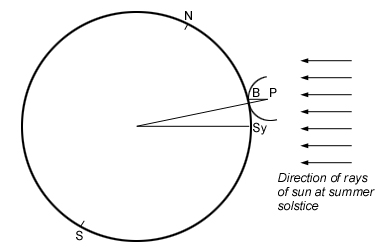

The method of Eratosthenes depends on a geometrical argument and gives the impression of being slightly more difficult to follow. But his statement will be made clear if we premise the following. Let us suppose, in this case too, first, that Syene and Alexandria lie under the same meridian circle; secondly, that the distance between the two cities is 5,000 stades; and thirdly, that the rays sent down from different parts of the sun on different parts of the earth are parallel; for this is the hypothesis on which geometers proceed. Fourthly, let us assume that, as proved by the geometers, straight lines falling on parallel straight lines make the alternate angles equal, and fifthly, that the arcs standing on (i.e., subtended by) equal angles are similar, that is, have the same proportion and the same ratio to their proper circles—this, too, being a fact proved by the geometers. Whenever, therefore, arcs of circles stand on equal angles, if any one of these is (say) one-tenth of its proper circle, all the other arcs will be tenth parts of their proper circles.

Any one who has grasped these facts will have no difficulty in understanding the method of Eratosthenes, which is this. Syene and Alexandria lie, he says, under the same meridian circle. Since meridian circles are great circles in the universe, the circles of the earth which lie under them are necessarily also great circles. Thus, of whatever size this method shows the circle on the earth passing through Syene and Alexandria to be, this will be the size of the great circle of the earth. Now Eratosthenes asserts, and it is the fact, that Syene lies under the summer tropic. Whenever, therefore, the sun, being in the Crab at the summer solstice, is exactly in the middle of the heaven, the gnomons (pointers) of sundials necessarily throw no shadows, the position of the sun above them being exactly vertical; and it is said that this is true throughout a space three hundred stades in diameter. But in Alexandria, at the same hour, the pointers of sundials throw shadows, because Alexandria lies further to the north than Syene. The two cities lying under the same meridian great circle, if we draw an arc from the extremity of the shadow to the base of the pointer of the sundial in Alexandria, the arc will be a segment of a great circle in the (hemispherical) bowl of the sundial, since the bowl of the sundial lies under the great circle (of the meridian). If now we conceive straight lines produced from each of the pointers through the earth, they will meet at the centre of the earth. Since then the sundial at Syene is vertically under the sun, if we conceive a straight line coming from the sun to the top of the pointer of the sundial, the line reaching from the sun to the centre of the earth will be one straight line. If now we conceive another straight line drawn upwards from the extremity of the shadow of the pointer of the sundial in Alexandria, through the top of the pointer to the sun, this straight line and the aforesaid straight line will be parallel, since they are straight lines coming through from different parts of the sun to different parts of the earth. On these straight lines, therefore, which are parallel, there falls the straight line drawn from the centre of the earth to the pointer at Alexandria, so that the alternate angles which it makes are equal. One of these angles is that formed at the centre of the earth, at the intersection of the straight lines which were drawn from the sundials to the centre of the earth; the other is at the point of intersection of the top of the pointer at Alexandria and the straight line drawn from the extremity of its shadow to the sun through the point (the top) where it meets the pointer. Now on this latter angle stands the arc carried round from the extremity of the shadow of the pointer to its base, while on the angle at the centre of the earth stands the arc reaching from Syene to Alexandria. But the arcs are similar, since they stand on equal angles. Whatever ratio, therefore, the arc in the bowl of the sundial has to its proper circle, the arc reaching from Syene to Alexandria has that ratio to its proper circle. But the arc in the bowl is found to be one-fiftieth of its proper circle.3 Therefore the distance from Syene to Alexandria must necessarily be one-fiftieth part of the great circle of the earth. And the said distance is 5,000 stades; therefore the complete great circle measures 250,000 stades. Such is Eratosthenes’ method.

Translation of T. L. Heath